Health CO-OPs of the Affordable Care Act

Promise and Peril at the 5-Year Mark

Allan M. Joseph, BA; Eli Y. Adashi, MD, MS - Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island

JAMA. Published online January 29, 2015.

In the early stages of drafting what would become the Affordable

Care Act (ACA), the notion of including a federal health insurance issuer in the

online marketplaces engendered an intense debate.1

Advocated with a goal of promoting choice and competition, the so-called public

option was to focus on the individual and small business markets.1 But it was not to be. Opposed by the health

insurance industry, characterized as a ggovernment takeoverh of health care, and

weighed down by concerns about a national single-payer health insurance system,

the public option proved unpassable.1 In its stead emerged the far less expansive if

politically palatable Consumer Operated and Oriented Plan (CO-OP)

program.2 The

nongovernmental, state-delimited CO-OP program was to gfoster the creation of

qualified nonprofit health insurance issuers to offer qualified health plans in

the individual and small group markets.h3

However, the CO-OPs (health insurance providers) should not be confused with

accountable care organizations (coordinated health care providers). In this

Viewpoint, we review the central tenets of the CO-OP program, assess its current

state of implementation, and describe its future

challenges.

As per statute, the state-chartered and -licensed CO-OPs

(freestanding distinct health insurance issuers) were to constitute private,

tax-exempt, consumer-operated and governed health insurance cooperatives.2 Modeled on member corporations

in the agricultural, utility, and financial sectors, the exchange-certified

CO-OPs were to issue at least two-thirds of all policies with the individual or

small-group markets in mind.3 Among the qualified health plans offered, at

least 1 was to feature gsilverh and ggoldh benefit packages whether on or off

the federal or state exchanges (government-run marketplaces of health insurance

plans).3 Encouraged to

operate statewide, CO-OPs were to establish integrated care models, develop

innovative (cost-saving) pay models, advance novel benefit designs, cultivate a

strong consumer focus, and incentivize wellness promotion.3 In particular, CO-OPs were to reinvest most net

earnings with the best interest of their membership in mind. Examples include

lowering premiums, expanding benefits, and improving quality.3 Low overhead costs were to be advanced by

reliance on private purchasing councils, preferred vendors, and grassroots

marketing efforts.3

It was the hope and expectation of the framers of the CO-OP

construct gthat there is sufficient funding to establish at least one qualified

nonprofit health insurance issuer in each State.h3

With this objective in mind, the CO-OP program was to be launched with 5-year

start-up and 15-year solvency low interest loans issued by the Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services.3 However, 3 sequentially enacted statutes later,

the ACA-proscribed budget of $6 billion has been reduced to $2.1 billion,

thereby all but eliminating the prospect of a nationwide CO-OP program.1,2

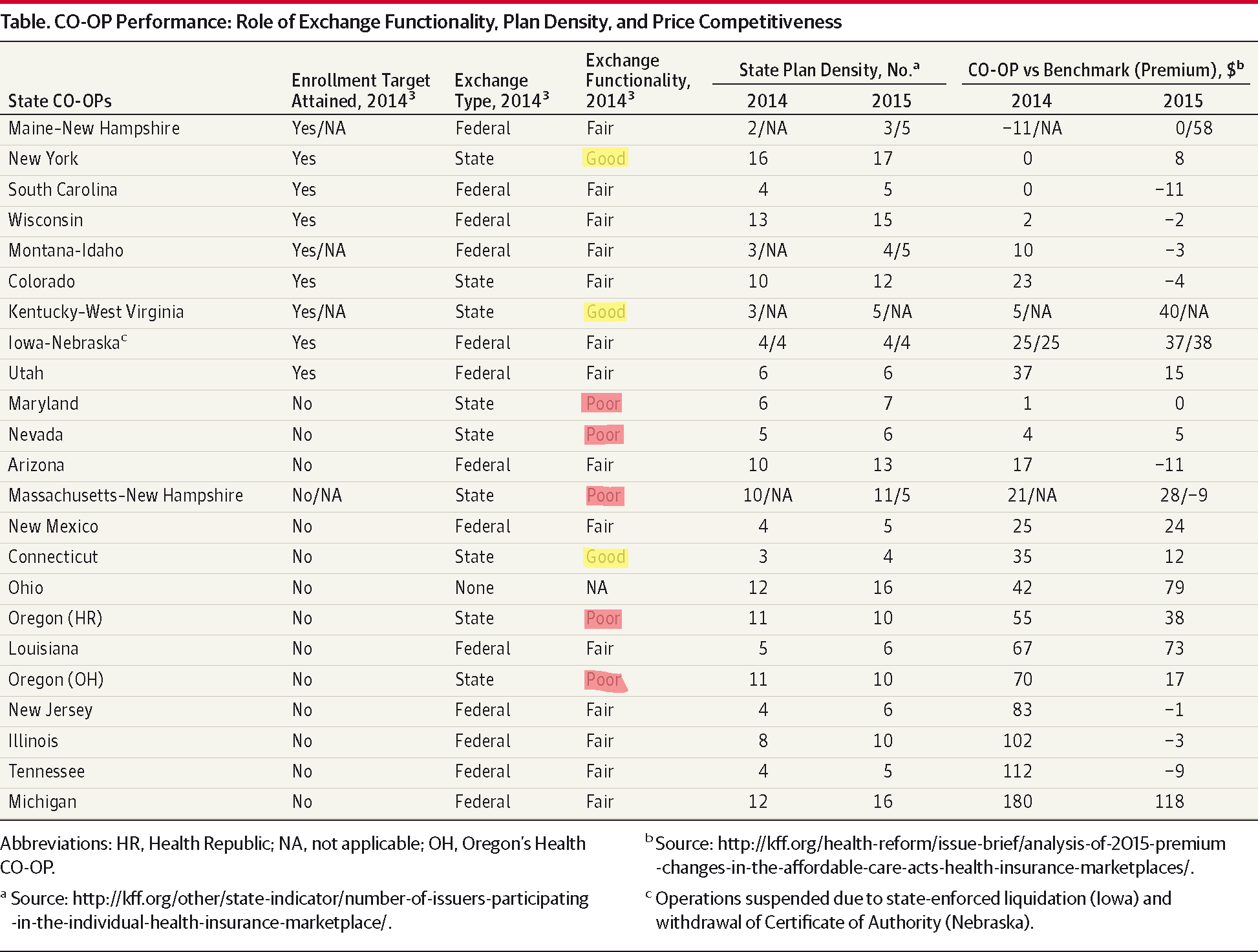

In the aftermath, a total of 23 state-based (private, not-for-profit) CO-OPs

have emerged.1,2 More recently, the national

complement of CO-OPs expanded to include New Hampshire, West Virginia, and Idaho

(Table) by way of newly launched

bi-state tandems (ie, CO-OPs serving 2 adjacent states, such as Kentucky–West

Virginia, Massachusetts–New Hampshire, and Montana–Idaho). In so doing, the

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services extended the reach of the CO-OP

program to a total of 26 states (Table) comprising an estimated 45% of the US

population.

gå}

By the end of the first ACA open-enrollment period (March 31,

2014), the 23 operational CO-OPs enrolled approximately 460 000 members, or 80%

of the total projected.4

However, the state enrollment records proved highly variable.4 Although 60% of the CO-OPs failed to reach

enrollment targets by wide margins, 40% either met or substantially exceeded

projected enrollment goals.4 The CO-OPs based in New York, Iowa-Nebraska, and

South Carolina alone accounted for more than half of all enrollees.4 What is more, CO-OPs based in

Kentucky and Maine dominated their online marketplaces, capturing 75% and 80% of

the market, respectively.

Viewed in hindsight, the 2014 enrollment record of a given CO-OP

appeared to depend on local determinants such as exchange functionality and

price competitiveness (Table). State

plan densities (ie, number of health insurance plans per state) appeared to have

played a more limited role. Overall, it appears that the CO-OPs have injected

welcome measures of choice and competition into the health insurance

marketplace. First, the CO-OPs introduced more products than any other new

entrant.5 Second, the

CO-OPs offered 37% of the lowest-priced plans in their home states.5 Third, premium rates were 9%

lower in states featuring a CO-OP as compared with states without one.5 More recent analysis suggests

that the CO-OPs have further increased their competitiveness on entry (November

15, 2014) into the second open-enrollment period. Relative to 2014, the premiums

of 10 rather than 3 CO-OPs are at or below the subsidy-determining benchmark

plan (gsecond-cheapest silver premiumh). However, increased plan densities in

virtually all states may pose an increasingly important challenge to the

CO-OPs.

Having crossed the start-up chasm with time to spare to loan

repayment (a 15-year horizon), the CO-OPs now face the imperative of growth to a

critical size compatible with sustainable ongoing operations. This requirement

is readily inferred from the experience of surviving legacy health CO-OPs (eg,

Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound), some of which have in excess of

600 000 members.6 Absent

such economies of scale, access to new capital, or both, the newly established

CO-OPs may be unable to maintain liquidity, disperse risk, lower premiums,

exercise leverage, and establish branded statewide integrated care models.

Moreover, CO-OPs gtoo small to thriveh may default on their loans. Viewed in

this light, the road ahead is clear in calling for aggressive recruitment of

enrollees through competitive pricing and product diversification.7 Far less clarity exists with respect to the

possibility of adverse future legislative actions. At the very least, the CO-OPs

will remain under scrutiny by the House Committee on Oversight and Government

Reform, which has launched an investigation of the CO-OPs to examine the

gObamacare loan Guarantee Gambleh as a case study of gpolitical influence

peddlingh and gtaxpayer dollars wasted.h

At this time, the future of the existing CO-OP program remains

promising if uncertain. According to this view, some CO-OPs may falter. The

recent default of CoOpportunity Health, the CO-OP serving the states of Iowa and

Nebraska, is supportive of this outlook.8

Other CO-OPs may experience a significant growth spurt replete with the related

attendant benefits. The latter outcome hinges on the appeal of the CO-OP

construct, functional online exchanges, and priced-to-compete multiyear

products.7 Growth by way

of entry into the mid-size and large group markets must also be

considered.7 In the final

analysis, the CO-OPs will have to prove their effectiveness and value in the

marketplace. Only time will tell if the gCO-OP optionh—rising as it were from

the ashes of the public option—will in effect constitute a worthy successor to

its much-maligned forebear.

Corresponding Author: Eli Y.

Adashi, MD, MS, Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, 101 Dudley St,

Providence, RI 02905. (eli_adashi@brown.edu).

Published Online: January 29,

2015. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.501.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form

for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Funding/Support: Mr Joseph is

supported by a Summer Research Assistantship (SRA) from the Warren Alpert

Medical School, Brown University.