PDF

of this report (4pp.)

By Paul N. Van

de Water

Updated October 12, 2013 - Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Congressional Republicans are reportedly considering whether to add — to

legislation to reopen the government and raise the debt limit — a measure to

raise the threshold for full-time work under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) from

30 to 40 hours. Thatfs because the ACA requires employers with at least

50 full-time-equivalent workers to offer health coverage to full-time employees

or pay a penalty, and critics claim the requirement creates a disincentive to

hire full-timers, prompting a shift to part-time work thatfs already evident in

the data.[1]

Recent data, however, provide scant evidence that health reform is causing a

significant shift toward part-time work, and therefs every reason to believe

that the ultimate effect will be small as a share of total employment.

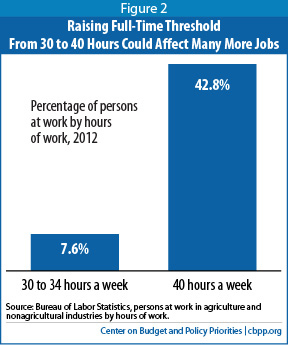

Moreover, raising the lawfs threshold for full-time work from 30 hours a

week to 40 hours would make a shift towards part-time employment much more

likely — not less so. Thatfs because only a small share of workers today

— less than 8 percent — work 30 to 34 hours a week and thus are most at risk of

having their hours cut below health reformfs threshold. In comparison, 43

percent of employees work 40 hours a week, and another several percent work 41

to 44 hours a week. Thus, raising the threshold to 40 hours would place

more than five times as many workers at risk of having their hours

reduced.

Data Donft Support Claim of Big Shift to Part-Time Work

The share of part-time jobs rose sharply during the recent recession, as it

does in every recession — employers cut workersf hours when demand for the

firmfs products or services weakens. Has this share continued to grow as

we approach the start of the ACAfs employer mandate, which was recently pushed

back a year to 2015? The answer is no. Part-time workers represent

18.9 percent of total employment — below the post-recession peak of

20.0 percent and the same as a year ago.[2]

Since President Obama signed health reform into law in March 2010,

civilian employment has grown by 5.4 million, and over 90 percent of the

increase is among people who usually work full time.[3] Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San

Francisco have concluded that gpart-time work is not unusually high compared to

levels observed in the past, most notably in the aftermath of the early 1980s

recession.h[4]

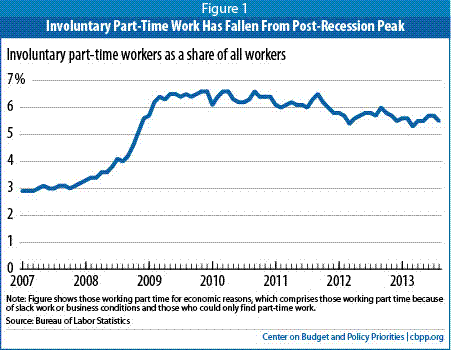

A more rigorous test

examines the recent trend in the share of involuntary part-timers — workers

whofd rather have full-time jobs but canft find them.[5] If health reformfs employer mandate were

distorting hiring practices in the way critics claim, wefd expect the share of

involuntary part-timers to be growing. Instead, as shown in Figure 1, it

is down about one percentage point from its peak.

Nor do the employment data provide any evidence that employers have cut

workersf hours below 30 hours a week to avoid the requirement to provide health

insurance. During the first half of this year, the share of workers

putting in 30 or more hours a week actually rose to 80.7 percent from 80.2

percent in the comparable part of 2012. Although the increase is small, it

refutes the claim that shortening of the workweek is widespread.[6]

To be sure, some employers have announced they are cutting certain employeesf

hours to avoid the requirement to provide health coverage to full-time workers,

but they are the exception. A small survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of

Minneapolis finds that only 4 percent of companies had shifted to more part-time

workers in response to health reform.[7]

Most recently, health-reform critics point to an increase in part-time work

in June and July as evidence of the lawfs impact. Thatfs highly

unconvincing, for several reasons.

First, therefs simply too much noise in the monthly data to attribute

short-term changes to a mandate that (a) most employers donft yet understand

well and (b) wasnft originally scheduled to kick in until next January.

Moreover, the number of people working part-time involuntarily gfor economic

reasonsh dropped substantially in August, almost entirely offsetting

the increases in June and July.

Second, furloughs prompted by the sequestration have moved many federal

workers into the part-time category in recent months. Almost 200,000 federal

workers were forced to work shorter hours in July — up from 55,000 a year

previously.[8] That has

nothing to do with health reform.

Third, when you observe trends over longer periods, some signs point in the

opposite direction. Since the trough of the recession in June 2009, for

example, the length of the average work week has returned to roughly its

pre-recession level.

The fact is, itfs too early to know how health reform will ultimately affect

the amount of part-time work. But therefs every reason to expect the

impact to be small as a share of total employment.

In particular, there simply arenft as many would-be part-timers as the

critics expect: fewer than 8 percent of employees work 30 to 34 hours a

week (and thus would be easiest for employers to shift below 30 hours).

Moreover, fewer than 1 percent of employees work 30 to 34 hours a week

and are employed by businesses affected by the employer mandate

and do not have insurance.[9]

And only some of these workers would likely be at risk of having

their hours cut.

gRecent research suggests that the ultimate increase in the incidence of

part-time work when the ACA provisions are fully implemented is likely to be

small, on the order of a 1 to 2 percentage point increase or less,h according to

economists at the San Francisco Federal Reserve. This conclusion is

consistent with the example of Hawaii, where part-time work increased only

slightly in the two decades following enforcement of the statefs employer

health-care mandate.h[10]

Since 1975, Hawaii has required nearly all employers to provide health insurance

to employees who work 20 hours or more a week for four consecutive weeks.

Employers must pay at least half the premium, and the employeefs contribution

must not exceed 1.5 percent of wages.

Finally, low-wage, part-time workers who work less than 30 hours a week will

be eligible for subsidies to purchase health insurance in the ACAfs new health

insurance exchanges (also known as marketplaces). For many of these

workers, the value of this health insurance subsidy will more than make up for a

loss in earnings from working slightly fewer hours.

Raising Threshold to 40 Hours Would Make Shift to Part-Time Work More

Likely, Not Less

Some legislators have

proposed raising the cutoff for the employer mandate from 30 hours a week to 40

hours.[11] That change,

however, would make a shift towards part-time employment much more

likely — not less so. Since 40 hours is the typical work week, employers

could easily cut back large numbers of employees from 40 to 39 hours so they

wouldnft have to offer them health coverage. The result would be

substantially less employer-sponsored health coverage — and as a result, a

potentially large increase in federal spending for the premium tax credits

that many low- and moderate-income people will receive under health reform to

help them buy coverage through the health insurance exchanges.

As Figure 2 shows, only about 8 percent of employees work 30 to 34 hours a

week (at or modestly above the ACAfs 30-hour threshold), but 43 percent

of employees work 40 hours a week and would be vulnerable if the threshold rose

to 40 hours. Another few percent of employees work 41 to 44 hours a

week. Thus, more than five times as many workers would be at risk of

having their hours reduced if the standard for full-time work went from 30 to 40

hours.

Health reformfs employer mandate is likely to have some effect on hours

worked, but it hasnft yet shown up in the data. Moreover, since few

workers without health coverage are near the 30-hour cutoff, the

employer mandate is very unlikely to prompt much of a shift toward part-time

work even when it takes effect. Raising the cutoff to 40 hours, however,

could turn the misleading claims of health reformfs critics into reality.

End notes:

[1] Kaiser Family Foundation,

gEmployer Responsibility Under the Affordable Care Act,h updated July 15, 2013,

http://kff.org/infographic/employer-responsibility-under-the-affordable-care-act/.

[2] Bureau of Labor

Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,

Tables A-1 and A-7, persons at work part time for economic or noneconomic

reasons as a percentage of civilian employment. BLS defines part-time work

as less than 35 hours a week.

[3] Bureau of Labor

Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,

Tables A-1 and A-6.

[4] Rob Valetta and Leila

Bengali, gWhatfs Behind the Increase in Part-Time Work?,h Federal Reserve

Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, August 26, 2013, http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2013/august/part-time-work-employment-increase-recession/.

[5] Federal Reserve Bank of

St. Louis, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), Employment Level -

Part-Time for Economic Reasons, All Industries, http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/LNS12032194.

[6] Helene Jorgensen and Dean

Baker, gThe Numbers Are In,h Center for Economic and Policy Research, August 26,

2013, http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/cepr-blog/the-numbers-are-in-obamacare-increased-percentage-of-people-working-26-29-hours-a-week.

[7] Federal Reserve Bank of

Minneapolis, gSo far, few employers cutting workers to part time in response to

Affordable Care Act,h Fedgazette Roundup, March 20, 2013, http://minneapolisfed.typepad.com/roundup/2013/03/like-it-or-not-the-affordable-care-act-will-offer-an-interesting-economic-experiment-on-incentives-or-punishments-dependin.html.

[8] Jackie Calmes and

Catherine Rampell, gU.S. Cuts Take Increasing Toll on Job Growth,h New York

Times, August 2, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/03/business/economy/us-cuts-take-increasing-toll-on-job-growth.html.

[9] Julie Rovner, gWill

Obamacare Mean Fewer Jobs?,h All Things Considered, National Public

Radio, July 30, 2013.

[10] Rob Valetta and Leila

Bengali, gWhatfs Behind the Increase in Part-Time Work?h

[11] H.R. 2575, The gSave

American Workers Act of 2013h; S. 1188, The gForty Hours Is Full Time Act of

2013.h